How did it start?

Following the speech, the director of our institute contacted my colleague, Artur Tarkhanyan, informing him of a government order to draft a proposal for an Armenian Genocide memorial project. Artur then approached me, shared the news, and suggested that we collaborate on the project. I accepted, although we were both in the dark about the details. During the USSR era, discussions on this topic were forbidden, with no literature available and no public coverage whatsoever. As we delved into our research, a sudden recollection struck me: my father, a teacher of Armenian language and literature, had a book titled “The Genocide of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire” on his bookshelf. Though I had noticed it before, I hadn’t paid attention to it. Arthur and I retrieved the book and began studying it together. With each turn of the page, a deep pallor overcame us, accompanied by an intense anger. We grasped the gravity of the topic and its significance. Now, the challenge lay in finding a way to encapsulate all that pain and tragedy within a memorial.

Shortly after, Anton Kochinyan, the first secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Armenia, invited us for a meeting. Hrachya Kochar and Paruyr Sevak were present at the meeting. To our surprise, we learned that we weren’t the only ones tasked with such an assignment; both the “Yerevan Project Institute” and “Hayart” had also been approached to propose a project. We were presented with two options: either create a park with one and a half million trees or design a monument. We were given a month to think and draft a sketch outlining what the monument could entail.

We immediately started working on the project. The municipality suggested the exact location where the monument currently stands, an empty area at the time.

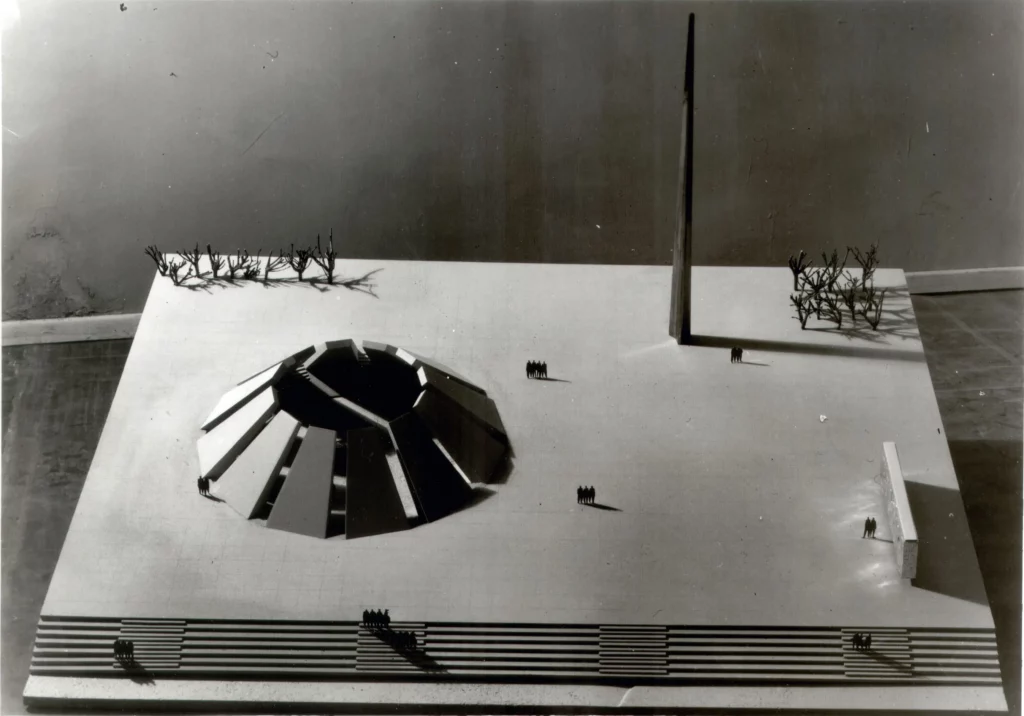

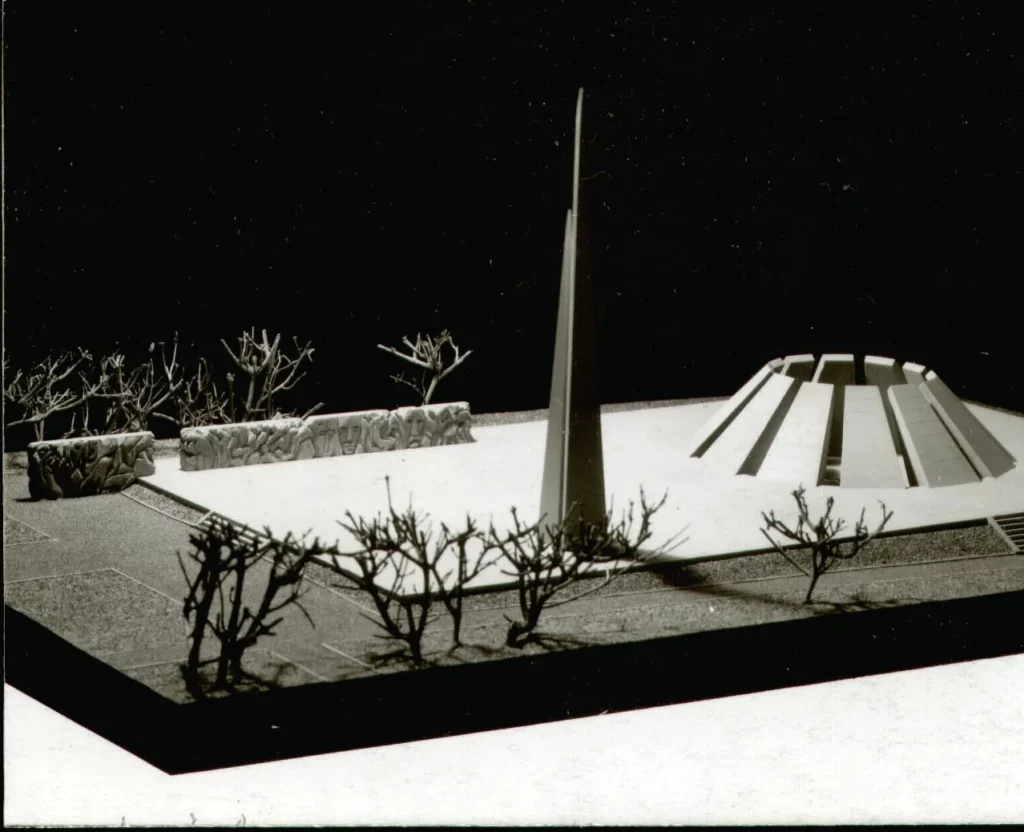

Our concept took shape: a colossal tombstone, beneath which a deep pit, nine meters in depth, would cradle an immense cross – a symbolic burial. Visitors would descend into the pit from one side and emerge from the other. We envisioned a small altar in this space, where a bell tower would stand, symbolizing the tolling bells during the days of the Genocide.

We prepared a sketch and a model of our design and presented it to Kochinyan. During the presentation, everyone involved was deeply immersed in the tragedy’s essence. I recall one participant suggesting a project structured around Dante’s nine circles of Hell. Visitors would descend a spiral pathway adorned with sculptures depicting scenes from hell.

After all the projects were presented, Kochinyan remarked that he now had a clear vision of the technical specifications for the monument competition. He emphasized the importance of not only commemorating the tragedy but also showcasing the rebirth of the Armenian nation. The monument needed to convey the message that despite all difficulties, Armenians have existed, currently exist, and will continue to exist.

About the contest

Artur Tarkhanyan and I decided to pursue a different approach for our second project. We recognized that a cross or a khachkar wouldn’t suit the intended purpose, as this wasn’t meant to be a religious structure or a church. With this in mind, we abandoned our initial idea and began exploring more discreet, minimalist solutions.

We proposed the concept of 12 columns, entirely monochromatic and devoid of any ornamentation. At the center would be the eternal flame, representing the resting place of the souls of one and a half million Armenians. Additionally, I suggested incorporating music to enhance the impact of the structure and its message. However, complications arose concerning the music selection. Demirchyan personally reviewed each composition and excluded those where the word “God” was mentioned.

This part represented the tragedy, whereas the other side was the memorial column with an asymmetrical appearance. It bore the semblance of a bifurcated stem emerging from the stone, symbolizing a struggle for sunlight.

In architecture, there exists a principle stating that when two asymmetrical structures are present, a third element is needed to balance them out. This role was fulfilled by the Wall of Mourning.

We submitted our project, not daring to hope it would be selected. However, soon after, Ara Harutyunyan, the sculptor of the “Mother Armenia”, reached out to inform us that our project had won the competition. With this news, we began drafting the working project, and by September, we commenced the construction phase.

About the construction

As per the project specifications, installing 12 large stones posed a challenge as cutting them to size proved impossible. We were presented with the options of either reducing the stone size or substituting it with concrete. However, we remained determined and eventually found a solution. During this time, I was appointed as an assistant to the quarryman at the Artik quarry. Through this role, I successfully managed to cut large stones from the first row of the mine.

The construction of the memorial faced various challenges, compounded by a tight deadline. It was determined that the structure needed to be completed by November 29, 1967. There were grounded concerns that we might not meet this deadline. To address this, L. Gharibjanyan, the secretary of the City Committee of Yerevan, appointed Karen Demirchyan, who served as the secretary of the City Committee at that time, to oversee the construction. With great responsibility, Demirchyan took charge of leading the construction of the memorial complex. Karen Demirchyan recognized the significance of erecting the Genocide monument for the Armenian nation. Every participant in the construction project felt a profound sense of duty in ensuring the timely and high-quality completion of the monument structure.

About the volunteers

Once the work was completed for the day, the volunteers gathered in the nearby grassy area, where they spread out the food, vodka, and wine they had brought. They ate, drank, and sang patriotic songs together. Most of these volunteers were the descendants of Genocide victims.

Prominent cultural figures such as Hayrik Muradyan, Paruyr Sevak, and Silva Kaputikyan also made regular visits to the construction site.

Opening Ceremony

“Today, we’re participating in the opening ceremony of yet another monument, which serves as both a tribute to the victims of the Turkish massacres and, at the same time, a symbol of the rebirth of socialism among our community”.

The opening ceremony commenced with the tolling of bells, and listeners tuning in via radio assumed that the memorial resembled a church.

I was eager to see how the event would be covered, so I was delighted when the headlines announced: “The memorial for the victims of the 1915 Great Genocide was opened”.

About the Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute

I initially opposed the idea of constructing the museum adjacent to the memorial complex, concerned that a larger structure would detract from the memorial’s impact. After extensive deliberations, we devised a solution to build the museum underground.

We presented this project to Levon Ter-Petrosyan, and it was promptly approved.

We were given 7 months to complete the project by April 24, and had to simultaneously manage the design and construction phases. Despite these challenges, we succeeded in our efforts. The museum was officially opened to the public on April 24, 1995.